"Systemic Change" Where It's Needed Most

A conversation with the people who know best how we can talk and work with each other for trust and lasting change.

Near the end of an almost hour-long conversation about race, equity, the healthcare industry and its systems — and where they all intersect but often fail to truly connect — John Gregory makes the point he most wants you to take away by asking the most fundamental question: "What systemic change will this make?"

Gregory has been working to bring change to systems — societies, really — for a quarter century, if not his whole life.

He's done that through building partnerships and bringing people together.

And the "this" here is another partnership, this time with Abbott — the first anchor sponsor of the American Diabetes Association's (ADA) Health Equity Now (HEN) platform — the ADA and Gregory's National Center for Urban Solutions (NCUS) to create the first community program under the HEN platform in Columbus, Ohio.

Gregory is president of NCUS, a company started as a workforce operation to help get people off welfare and back on the job. "We went to lots of meetings — lots of meetings — and all we heard about was problems," Gregory said. "And so I was like, hey, 'Where are the solutions?' " And so he got busy finding them.

In addition to NCUS, Gregory is also the founder of the African-American Wellness Agency, which has a mission to bring "attention and awareness to African-American disparities in health," Gregory said.

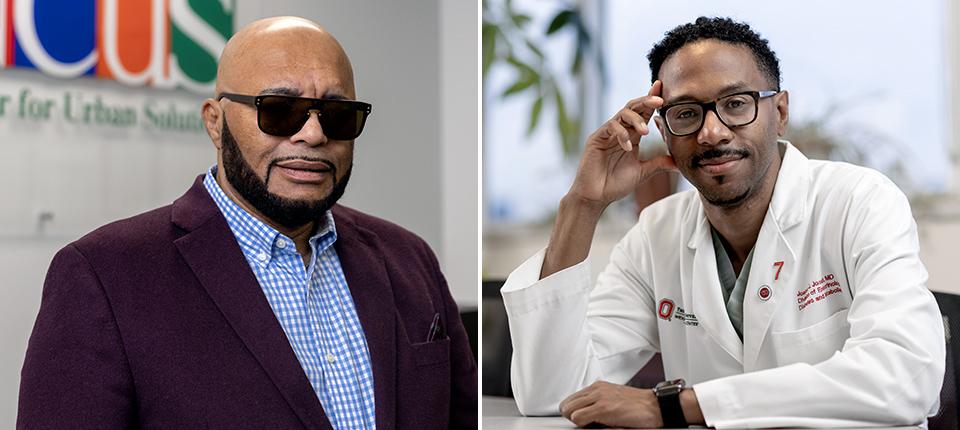

In that work — and in this conversation — Gregory is joined by Dr. Joshua Joseph, MD, MPH, FAHA from The Ohio State University with expertise in endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism.

This work is personal for these men.

Joseph is originally from Columbus and was, "drawn to health because of experiences in my own family, my own community including my grandmother having diabetes and giving herself insulin for many years and ultimately passing away from a heart attack," he said.

This program among NCUS, the ADA and Abbott will provide up to 150 Black adults living with diabetes in the Columbus community with health education and access to FreeStyle Libre, our glucose monitoring technology.

Beyond improving the health of participants, the program aims to better understand the barriers of access so in the future, diabetes care technology can reach everyone in need.

Because, as Gregory explains and Joshua agrees, "We know there's a tremendous trust issue between African-Americans and the medical field. And so what we think we do is we bridge that and we allow because we become partners with different organizations, now we can take the message and there's some message of trust."

Edited for length and clarity, what follows is that conversation among Gregory, Joseph and Abbott laying out the ground that's already been covered and the differences made, the possibilities before us and the challenges that all of us need to join together to overcome. Because, as we believe, a sustainable future starts with health.

Abbott: What are some of the efforts NCUS has undertaken with others to improve health in the community?

Gregory: We do walks — and actually they're 5K walks and runs — but the whole issue is around health, around Black men. Black men live two years shorter than white men. We’re really doing an awareness campaign to bring attention that Black men can live longer if they know their numbers and do the things they need to do. So we’re organizing communities and around those communities we have lots of African-American physicians participating.

We are doing fatherhood initiatives where we're working with Black fathers to make sure they get connected to their children.

We're doing mental health events.

We do a thing called Real Men, Real Talk.

We're doing mentoring programs.

And then we're doing opioid awareness. They discovered that the highest number of men overdosing on opiates are African-American men.

So those are the projects that we are doing as it relates to health. And then we've partnered with The Ohio State University for COVID mask campaigns, vaccine campaigns.

The reason Abbott and the American Diabetes Association are working with us is because what they found is that we can reach the communities who they cannot reach. And we can have the language and the conversations with the audience that they're trying to have and, therefore, the messaging becomes something that people can relate to.

We know there's a tremendous trust issue between African-Americans and the medical field. And so what we think we do is we bridge that because we become partners and can take the message, and there's some message of trust.

Joseph: So out of those walks, one of the things that they ask is, "Can we evaluate that data? Are Black men getting healthier?"

What we saw looking at data from 2015, '16, '17, '18 was that the men knew their numbers — so they knew their blood pressure, which is a huge win; they knew their cholesterol, huge win — but unfortunately those numbers weren't improving. Year after year with poor numbers.

So we put together a program called Black Impact, a 24-week program where we looked to recruit men who had poor cardiovascular health: blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, body mass index, poor levels of physical activity, diet or smoking.

They were put on six teams and each team had a health coach as well as a personal trainer. They went through a curriculum where they came out two hours per week. One hour was on health education and one hour was physical activity.

And a lot of Black men were frankly lonely. They didn't have those social connections.

And so throughout the program, what we saw was that the men were fantastically engaged in the program, enjoying the program, and out of that really building trust with the medical community as well as building trust with each other, which was just great to see.

At the end of the 24 weeks, men had lost weight, their blood sugars had improved, their cholesterol had improved, they were doing more physical activity. And so what we call "Life Simple 7" improved through the course of the study.

So through these collaborations, you're able to make a real difference in lives?

Gregory: Dr. Joseph uses this terminology, "clinic to community."

I think what we're doing is a real true example of clinic to community.

We have all these conversations around equity and it also often time appears people aren't listening because institutions don't do anything different. And what we've seen working with Dr. Joseph and his group is that they're doing something different. They are bringing the message to the community and then actually bringing the services to the community which is why we're seeing a lot more participation.

And that is kind of modeling the project with ADA and Abbott.

We're going to really make it a community-based program where we’re assigning wellness coaches, we'll be meeting with people on a weekly basis.

We're taking the things that we’ve learned in the Black Impact project and adding those things into this project, in which we will be also working with women.

We think we've learned some very valuable things and so again, the clinic is going into the community and will be functioning in the community.

You're able to open doors and build trust?

Gregory: We have a great reputation for being in the 'hood.

And so what it does is it gives Abbott and ADA an opportunity to be a part of true community work. The benefit is that we have been part of the planning.

Abbott, you have a certain language. ADA has a certain language. And then the community has a certain language. And one of the things we've been able to do is share information in context so that people begin to understand how things are communicated and understood. We gotta put it in the language that every day people can understand so it really reaches the community so they can interpret it how they need to interpret it so they can decide what's best for them.

Joseph: Abbott knows all too well that we have huge gaps in the prevalence of diabetes in this country with Black populations, as well as Hispanic-American populations have a much higher rate both in the development of diabetes every year as well as the total amount of individuals with diabetes in this country.

And the biggest gap though is the gap in mortality where Black Americans in this country are two times more likely to die from diabetes compared to White American populations.

When we think about that gap, one of the reasons is the difference in blood sugar control.

So when we look at a new device like a continuous glucose monitor, I see many individuals in clinic that are distrustful of that. "Well, why would I wear this? Why am I going to wear something that is on my arm always checking my sugars? Who's looking at that? What numbers and all those things?"

But we know from all the studies that continuous glucose monitors are a great advancement to improve glucose control.

So how do you break down those barriers and work across those silos to get a great advancement out to the people who need it most?

That is really the key to this project: Breaking down those barriers and working across those silos.

And I'm kind of laughing at what Mr. Gregory was saying because Mr. Gregory is one of these people, he's a translator, right?

'Cause us in the healthcare community, us in the biopharmaceutical, us in the biotechnical community and the community speak different languages, right? And Mr. Gregory and others like himself sit at the intersection of that and are able to translate back and forth in order to move forward and really address these inequities.

Everyone has metrics they use to gauge progress. How will you measure success, long-term and short-term?

Gregory: It really, to me, is a long-term commitment. That's how we will know we have impact: If we’re not having this conversation 10 years from now about equity.

The short-term? Can we get great outcomes from their participation and out of that can we change people's lives so that the use of FreeStyle Libre 2 that we’re going to be advocating, that now people see that as something that they can use for their everyday life. And now they've made a health change and they're spreading that message to the rest of the community and we can get the rest of the community to adopt it.

Joseph: Echo everything that Mr. Gregory said there, for sure.

For the short-term perspective, as an endocrinologist and diabetologist, my No. 1 will be improvements in the individuals who participate in the program as far as their blood sugar control.

And then an improvement in them in building a sense of community, which I think is just huge in diabetes treatment and control.

Long-term, from my perspective, is that we see more healthcare organizations breaking down the four walls of our health system and getting out into the community to address and engage around health.

If 10 years from now, our large health systems here in central Ohio and all the other areas around the country that we want to influence are out in the community and saying, "Hey, let's build these collaborations in the community to address diabetes or heart disease or asthma" or whatever the situation is, I think that that’s a win. Because that's what is different about this project.

How do we bring healthcare systems and clinics directly to the community to build that trust and really address those inequities that we've seen over previous years and decades.

As this project begins, what do you want us to keep top-of-mind?

Gregory: What's most valuable is that people understand how powerful and necessary it is that we not only talk about equity but put stuff into action. And the American Diabetes and Abbott, this has been them putting something into action that should get a long, sustaining result.

What is really needed are systemic changes. What systemic change will this make? Because that's what we're trying to do is make system changes.

Joseph: The biggest thing for me — and I see it more and more every day — is that we all come to the table.

We all are in this life, and we have certain skills, and we have certain expertise.

But to really solve these inequities, it's all about relationships and partnerships and collaborations and everyone bringing their best to the table.

Whether that's us here at Ohio State, whether that's the African-American Wellness Agency and NCUS, whether that's Abbott, whether that’s the American Diabetes Association, whether that's the men and women living in the community, right? Because they have a perspective that is critically important as well.

And those individuals living with diabetes and on their diabetes journey. It takes all of us to come to the table to figure this out and to work together and, as Mr. Gregory said, put together projects that will advance to equity in the treatment and care of diabetes.