Bayer: Where Does Food Go From Here?

Envisioning a more nimble supply chain

Before COVID-19, the food supply chain we relied on was a long one. Trillions of dollars worth of food criss-crossed oceans and highways at the speed of our appetites. And it worked for many. Our staples were made available where and when we wanted them. But, with the global pandemic, that chain was rattled.

We all saw images of farmers forced to destroy their harvests, while lines at food banks grew longer. Grocery store shelves went bare. And food prices went up.

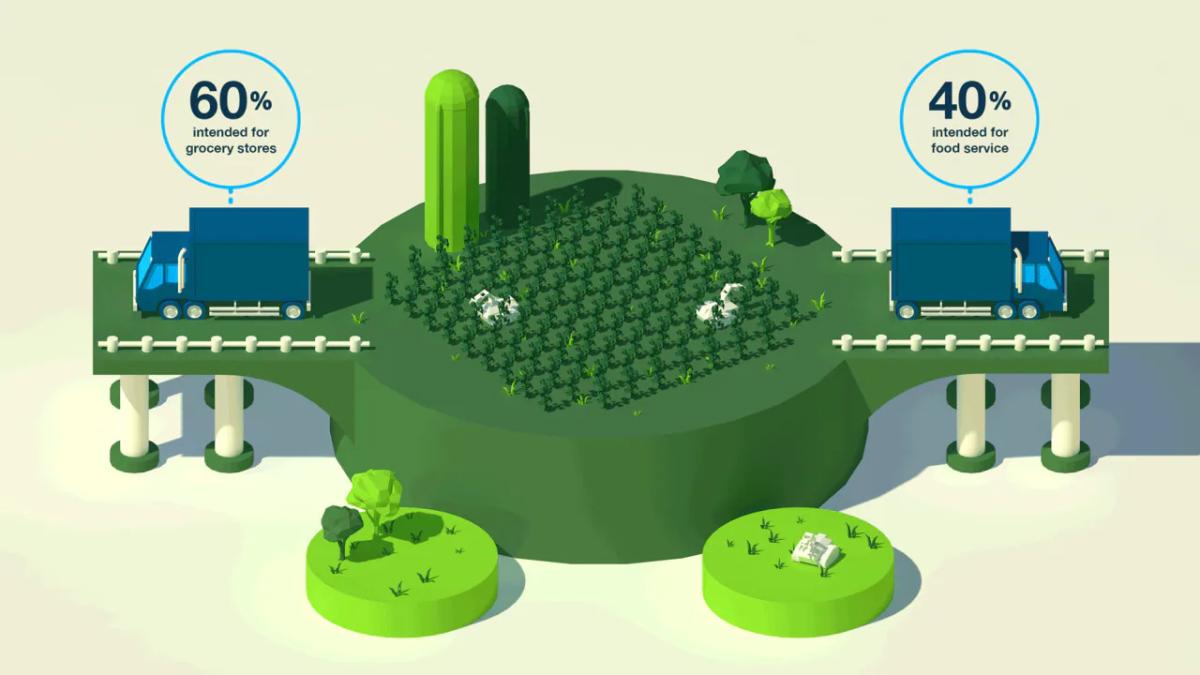

Many factors contributed to the disconnect. For one, our pandemic-era consumption has changed where we buy our food, therefore changing what we eat.

Because crops and livestock are produced, processed, packaged, and shipped in very specific ways to meet very specific demands, our changing buying habits meant some food intended for schools and restaurants couldn’t be sold. Suppliers had to reroute food rapidly. And while tons of waste was avoided thanks to fast action and digital insights, some harvests were left in fields to rot.

We also have to remember that much of our food comes from very far away. Our globalized system brings people fresh meat and produce year round, and allows for access to food that simply wouldn’t grow locally. For example, bananas struggle to grow in Canada, yet currently, Canadians eat 3 billion of them a year.

Our global system has its advantages under normal circumstances. But these aren’t normal circumstances. When the pandemic hit, borders closed. Plane, train, truck, and boat shipments were stopped mid-transit, and food couldn’t get where it was intended to go.

When as much as 80% of the food consumed around the world is imported from other countries, closed borders are more than an inconvenience. They’re dangerous. Especially when combined with rising unemployment.

And in developing countries where the food supply chains are already fragile, and hundreds of millions of people rely on agriculture for their livelihoods, the pandemic limited access to credit, slowed the transportation of goods, and froze incomes.

But, you can’t plan for a pandemic. Or can you? The big question now is—Where does food go from here?

Seeds of Stability

The supply chain starts with seeds. What if we could make them more resilient?

A.D. Alvarez is a leader on his island. And a bit of a pioneer. He farms in the Philippines, and though his corn operation is relatively large, the majority of his neighbors’ farms are less than a hectare in size.

Alvarez says many of the other farmers on his island rely on imported food. They can’t grow enough to sustain themselves or make a viable living from farming. And that was before the shutdown.

“We never prepared for something like this,” he says.

"There's a saying in the Philippines: When your blanket is too short learn to bend your legs."A.D. Alvarez, the Philippines

The majority of farms on his island are like small blankets, but what if we could find ways to fit more underneath?

“I started introducing Bt corn on the island. Because we wanted to test it first,” says Alvarez.

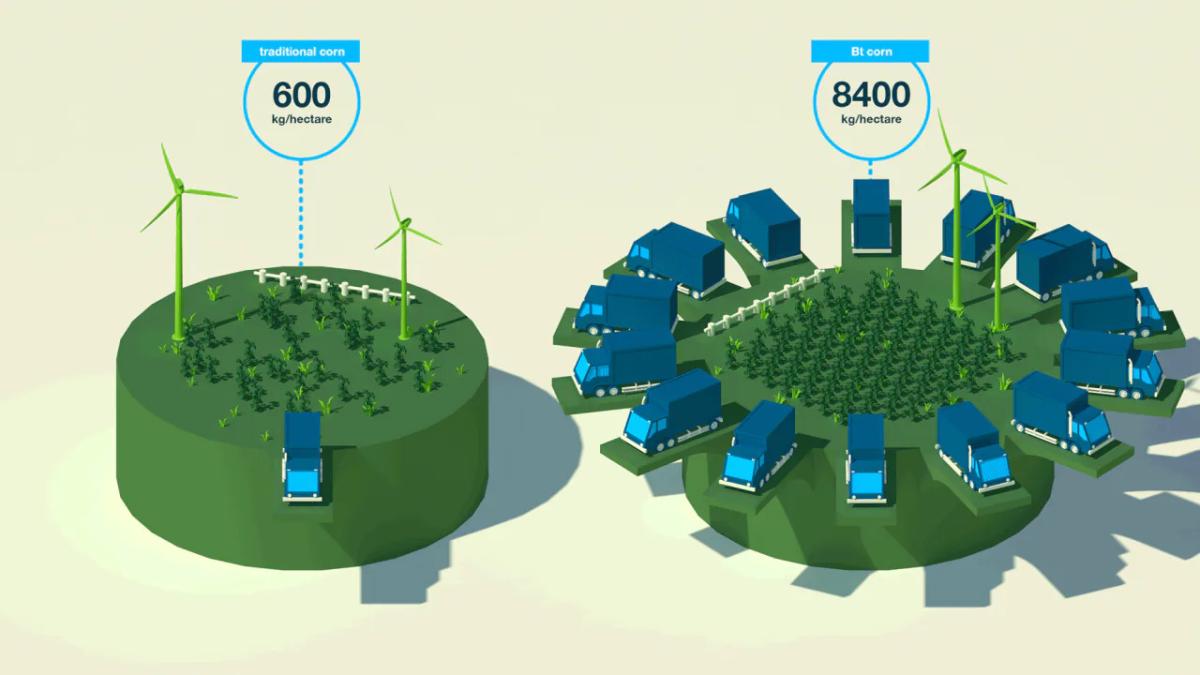

This type of genetically modified corn is higher-performing and more resistant to pests. In the Philippines, corn farmers with small landholdings traditionally see a harvest of about 600 kilograms per hectare. Alvarez’s first harvest using Bt corn was about 14 times that.

It’s clear to Alvarez and other community leaders that access to this type of innovation could mean real economic and social progress for the families in his municipality. Especially during a pandemic.

“At the end of the day, we have to give our farmers the tools they need,” he says.

"Of course, I'm dreaming. But that's how innovations happen - when you start dreaming. Most people would say it's impossible. But we have put a man on the moon, and that was impossible. So we should really give the freedom to dream, and the tenacity to make it work.A.D. Alvarez, the Philippines

Bananas and Bandwidth

Digitizing our food system starts on the farm

New technology creates new realities. And the digitalization of agriculture is helping farmers around the world reimagine the way our food system works — and who works it.

“You need to keep young people working in rural areas. There is a lot of immigration from rural to urban areas because young people don’t think they have a future,” says Ronald Guendel, Global Head of Food Security and Advocacy at the Crop Science Division of Bayer.

Guendel has a lot of big ideas for improving our food system, and one of them is to embrace digital innovation. How does he think digital agriculture can engage a younger generation?

“You create a system where they feel needed. You create new enterprises where they can provide support,” he says.

And there’s no doubt they are needed. Climate change, food security, and growing global food demands are challenges that will have a disproportionate impact on younger generations.

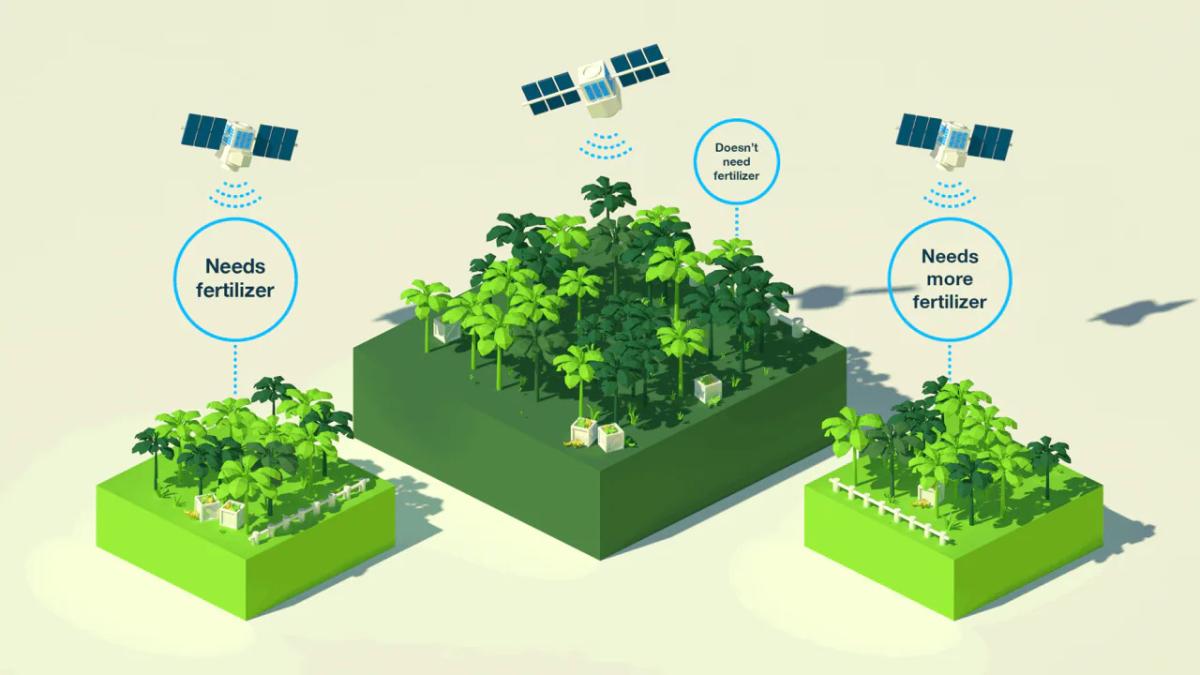

Guendel has seen progress in action. He recently visited a banana plantation in Ecuador and talked to a group of young farmers there who were leveraging satellite imagery to monitor their crops from space. They then used that data to apply nitrogen more precisely. This allowed them to use less fertilizer while seeing stronger harvests.

This type of sustainable solution—one that uses data to conserve resources—is on the rise in agriculture. But not all agtech orbits the earth. Robots are being tasked to plant, pluck, and protect crops all around the world.

“Some growers and farmers have been investing in technologies in the last several years and that’s paying off incredibly well right now,” says Cathy Burns, CEO at Produce Marketing Association, a trade organization that advocates for stakeholders all along the produce and floral supply chains.

Automation is reconfiguring our entire food system, not just farming. You may have seen it in your local grocery store. Retailers are using robots to monitor inventory, and even clean up spills.

Automation isn’t going anywhere. It’s going everywhere, including your doorstep.

“Over the past seven months, investors have pumped at least US $6 billion [5.3 billion euros] into more than two dozen companies involved in autonomous delivery of goods and foods,” says Burns.

And with all of this technology, comes data—numbers we can put to use up and down the food supply chain. These insights help tie the whole thing together, sustainably.

Collaboration is the New Currency

Traceability. It will truly create a more nimble food system

Whether it ends on a fork, between chopsticks, or between fingertips, food starts on a farm. And it takes a lot of people, time, and energy to get it from one place to another. But what if everyone tasked with growing, transporting, packaging, and selling food worked together for the sake of our planet and its people?

That’s what A.D Alvarez, Ronald Guendel, Cathy Burns and other experts want to see.

“Collaboration is the new currency,” says Burns. Collaboration along the entire food chain would mean reducing waste. It would mean better visibility for consumers. It would mean more reliable markets for farmers. And it could mean more flexibility during a public health emergency.

"This will certainly help if we're hit with another pandemic. But even as we look at crises from shortages of product, to produce safety outbreaks, leveraging technologies like blockchain will become more and more important to be able to trace back product all the way to the farm."Cathy Burns, United States

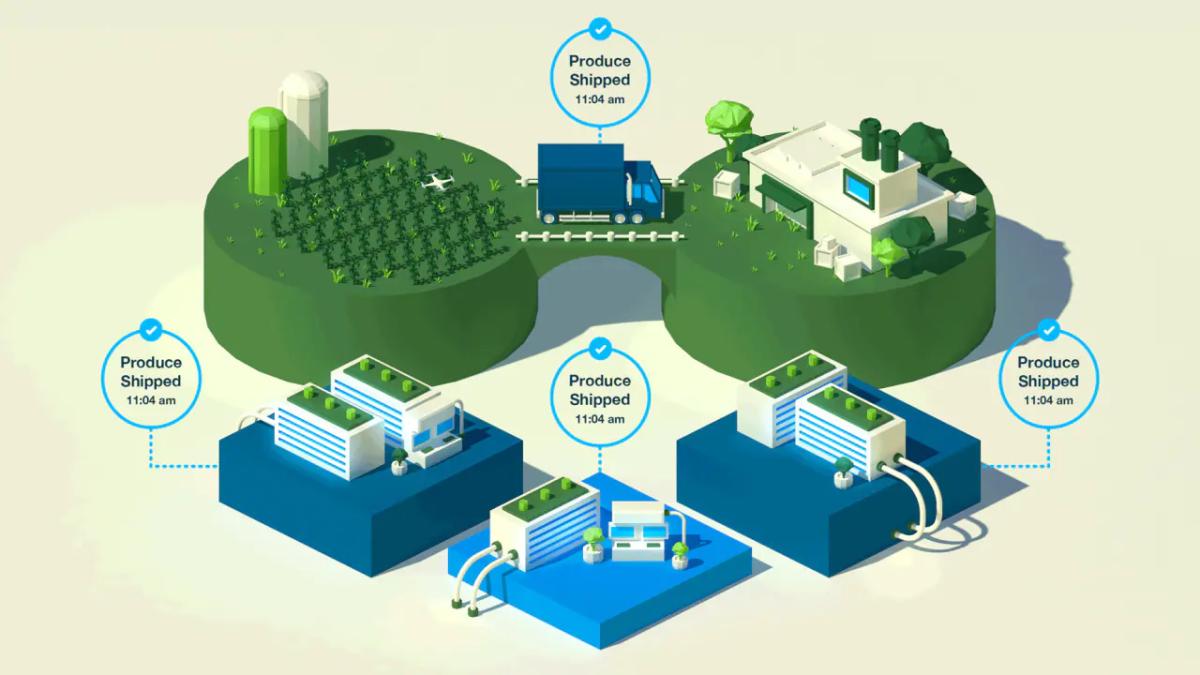

Blockchain is a decentralized ledger technology where everyone along the supply chain, from farmers to grocers—and every supplier in between—tracks products as they move chronologically. When one stakeholder updates information about a piece of produce, everyone else has access to that data. Food becomes traceable.

In a reimagined supply chain, seed companies work with farmers to solve problems for processors, grocers, and ultimately consumers.

Take strawberries for example. In the near future, autonomous strawberry pickers will roll through row after row of green leaves, sensing and scanning for the perfect berry. It’s the type of technology Cathy Burns says farmers are investing in because it has the potential to solve important challenges like supplementing labor when there is a shortage, making easier work of a typically intensive manual process, and helping to keep farm workers safe.

However, plucking a delicate berry with a robotic arm takes cutting-edge precision, and a hearty berry. What if seed companies could make it a little easier on the roboticists?

“It’s another opportunity to work upstream with a company like Bayer. To determine, what’s the breeding capability we need? Could we have a hearty strawberry that’s incredibly flavorful? That actually enhances the consumer experience?” Burns wonders.

"It's been heart-warming over the last three months. The openness, the transparency, the candor to come together to address the systemic issues. That will have long-term positive effect."

Cathy Burns, United States

Innovation. More Than Ever.

To stabilize our supply chains and support the communities that depend on them, we’ll need to lean into the solutions we strived toward in 2019 even more in 2020, and beyond. That means accelerating innovation. Not stalling it.

What we need now is an open-arms type of globalization, where we share ideas to end the pandemic and to get through it.

“Of course, I’m dreaming,” says A.D. Alvarez from his farm in the Philippines. “But that’s how innovations happen—when you start dreaming. Most people would say it’s impossible. But we have put a man on the moon, and that was impossible. So we should really give the freedom to dream, and the tenacity to make it work.”

View original content here